Written by

Published on

TLDR; MakoraGenerate implements Kimi Delta Attention kernels that outperform PyTorch by 5-7x and match expert-written kernel latency on some shapes. The kernels are available for inspection here.

The attention mechanism is among the most important building blocks of deep neural networks. Despite the original implementation’s success, its quadratic compute cost and linear memory footprint have motivated a wave of more efficient variants. The research community has responded with increasingly sophisticated designs, such as Kimi Delta Attention (KDA) from the Kimi-K2 model [1], that offer substantial theoretical and empirical advantages. However, these variants often lie outside the optimization envelope of PyTorch and even torch.compile, requiring bespoke, hand-tuned GPU kernels that only a small number of experts can produce. This dependency on specialized kernel engineering has become a key bottleneck, limiting how many attention variants can be implemented, evaluated, and scaled in practice.

This blog post shows how MakoraGenerate (formerly MakoGenerate), our LLM coding agent for writing GPU kernels, overcomes this bottleneck. By exploring KDA, the core mechanism behind Moonshot AI’s Kimi Linear architecture [2], we dissect why standard compilers struggle, how expert Triton kernels overcome those limitations, and how MakoraGenerate automatically produces kernels that match expert-level performance in minutes, rather than the days or weeks required by manual engineering. This introduces a new paradigm that allows us to explore new attention variants at a rate that was never before possible.

The Kimi Delta Attention (KDA) Algorithm

To understand the optimization challenge, we first need to understand the math. Unlike standard attention, which computes an O(T²) similarity matrix, KDA maintains a fixed-size state:

Which compresses history, making it a linear attention mechanism that formulates context processing as a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). It refines the delta rule, which updates the state based on the error between actual and predicted values, by adding fine-grained, channel-wise gating. The recurrent update rule proceeds in three steps:

Step 1 — Decay (forget old information):

Step 2 — Predict & Correct (delta rule):

We first estimate the value using the decayed state, then compute the error to update the state.

Note: This assignment defines the new state used for the next time step.

Step 3 — Output (read from memory):

Where:

This predict-then-correct mechanism is what gives KDA its name. It applies the delta rule from neural network learning, treating the state matrix as an associative memory that continuously refines itself.

The Hardware Challenge

Mathematically, this is elegant. Computationally, it is a memory transfer nightmare.

For inference, we use KDA's recurrent formulation rather than the chunked parallel version designed for training. In this mode, the state matrix S must be read, updated, and written back at every single token. This state is large: for typical head dimensions, S contains hundreds of thousands to millions of elements. In our test cases with K=256 and V=8192, that's 4MB of data per head.

A naive implementation treats each time step independently: read the entire state S from GPU global memory (HBM), perform a handful of arithmetic operations, then write the entire state back. The problem is that GPUs are designed for compute-heavy workloads, not repeatedly moving data back and forth. Modern accelerators like NVIDIA H100 can perform orders of magnitude more arithmetic operations than they can transfer bytes at the same time. With arithmetic intensity this low, the kernel spends most of its time moving data rather than computing, leaving the vast majority of the GPU's compute capability idle.

This is a classic memory-bound bottleneck. The state S makes a round-trip to HBM for every token in the sequence, and no amount of raw FLOPS can compensate for that bandwidth wall.

TorchInductor: Good, but not Enough

We ran a naive PyTorch implementation of KDA through torch.compile (using the default Inductor backend). While functional, it struggled to overcome the memory wall.

The compiler often fails to identify that is a transient accumulator that should live in the GPU's registers or Shared Memory (SRAM). Instead, it materializes the state to HBM at every step to ensure safety for the autograd graph. This results in the implementation running at a fraction of the hardware's peak throughput.

The Hand-Optimized Triton Solution

Expert kernel engineers solve this problem by allocating S in fast on-chip SRAM and keeping it there for the entire sequence, instead of reading and writing S from HBM every token.

The optimized Triton kernel declares the state as a Triton tensor, ensuring that it resides in registers or shared memory rather than global memory:

This restructuring significantly reduces memory traffic. The naive approach reads and writes S (8MB round-trip) for every token, totaling 8MB × T for a sequence of length T. The optimized kernel only reads inputs (q, k, v, g, beta) and writes outputs, roughly 50KB × T. That's approximately 160× less memory traffic for the same computation, pushing arithmetic intensity from 0.06 to nearly 10 FLOP/byte.

Beyond the fundamental SRAM insight, the kernel applies several additional optimizations. It parallelizes across batch, head, and V dimensions by launching a grid of (B × H, ceil(V / BLOCK_V)) thread blocks. Each block processes a BLOCK_K × BLOCK_V tile of the state matrix, sized to fit comfortably in registers. All four operations (decay, predict, write, read) are fused within a single loop iteration, eliminating intermediate stores. The kernel also uses FP32 accumulation for numerical stability, converting back to the original data type only when storing final outputs.

Generating an Expert-Quality Kernel Automatically

We tasked MakoraGenerate with optimizing KDA. We provide the Kimi Linear Attention paper and the reference PyTorch implementation as inputs, then compare the results to the hand-optimized kernels from the Flash Linear Attention (FLA) repository [3], as well as the performance of torch.compile in default mode. The full kernel generation run takes about 5 minutes to materialize a baseline, then iterates using evolutionary search to improve the kernel for an additional hour.

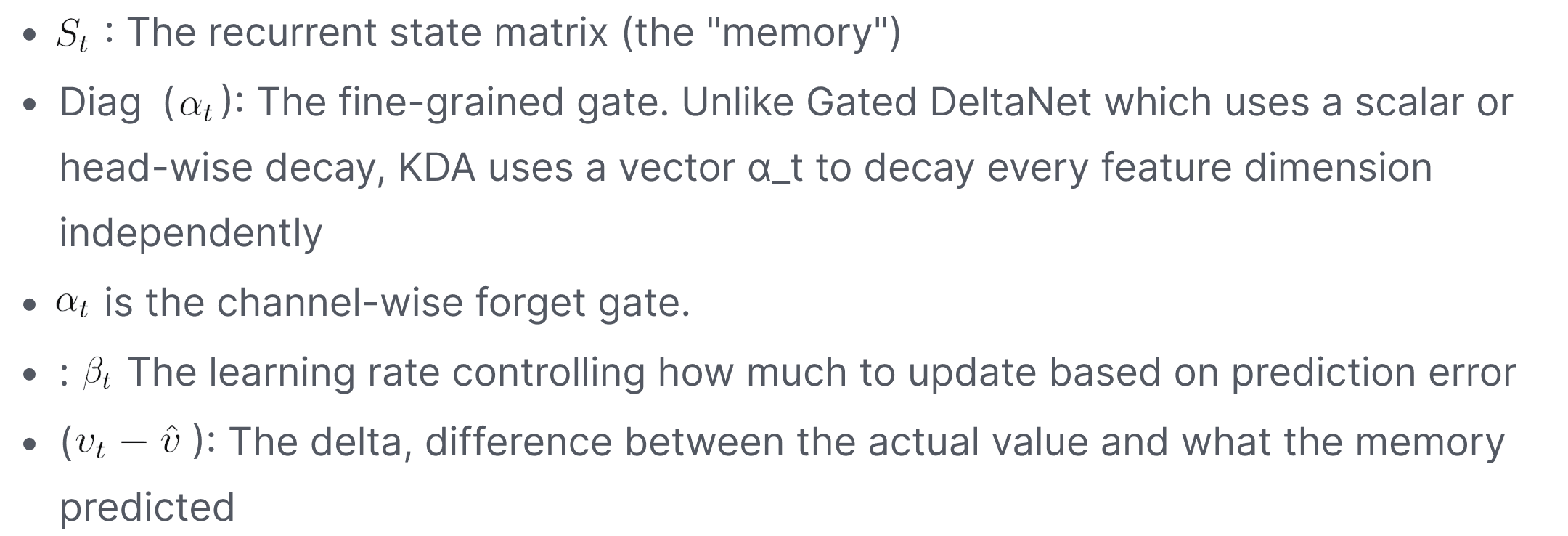

When a PyTorch reference problem is passed to MakoraGenerate, a user specifies input shapes to test against. In this example, we develop separate Triton kernels for each input shape, and for the NVIDIA H100 GPU. We choose four shapes that are relevant for low-to-medium context length use cases. Results are shown below.

Input x Output token lengths (K x V) | Use Case | Torch. | MakoraGenerate | Expert-Written |

|---|---|---|---|---|

256 x 8192 | Small reasoning | 1x | 5.8x | 5.8x |

512 x 16384 | Medium reasoning | 1x | 7.9x | 7.8x |

8192 x 1024 | Small RAG | 1x | 0.34x | ❌ Runtime Error |

16384 x 1024 | Medium RAG | 1x | 0.71x | ❌ Runtime Error |

We benchmarked performance using standard best-practice methodology (discard warmups, cache clearing, etc.), and the results show evidence that the agent can automatically generate kernels that match expert-level performance while substantially outperforming compiler-generated baselines. At K=256, V=8192, the agent delivered a 5.6x speedup over torch.compile matching the hand-tuned implementation; at K=512, V=16384, it achieved an even larger 7.8x speedup, again reaching parity with the expert kernel. These results demonstrate that the agent can reliably close the performance gap traditionally reserved for specialized human-engineered kernels.

Performance does decline on the largest shapes we tested: at K=8192, V=1024, throughput drops to 0.34× of the baseline, and at K=16384, V=1024 it reaches 0.71×. These shapes expose a clear frontier for further optimization, where larger K-dimensions make tiling, memory traffic, and register pressure more challenging.

However, what’s particularly noteworthy is that on these same large shapes, the hand-optimized FLA baseline fails entirely, hanging during kernel compilation with nvcc as its heuristics break down outside typical parameter regimes. The agent-generated kernels, by contrast, compile and run successfully, handling cases that human-designed heuristics cannot, even if performance remains below the expert baseline where it does succeed. This robustness underscores the agent’s ability not just to match human experts on favorable shapes, but to generalize beyond the reliability envelope of existing hand-tuned kernels.

Kernel Performance vs torch.compile

What the Agent Did Right

Examining the generated code reveals that the agent correctly identified memory bandwidth as the core bottleneck and applied the critical optimization of keeping state in SRAM across the time loop. The kernel structure mirrors expert implementations, with pre-computed base pointers outside the loop, proper tiling with BLOCK_K = next_power_of_2(K) and BLOCK_V = 128 , and carefully The agent also made subtle but important decisions around numerical stability. All computations happen in FP32 with explicit .to(tl.float32) conversions on load, and the scaling factor is applied directly to queries rather than being folded into a later operation. Boundary conditions are handled correctly with masks, preventing out-of-bounds memory access that could cause silent correctness issues.

Comparing the agent's output to the FLA baseline reveals an interesting tradeoff. The FLA implementation is more general-purpose, supporting multiple gating modes (scalar g, per-key gk, per-value gv), variable-length sequences, and optional initial/final state handling through extensive use of @triton.heuristics for conditional compilation. This flexibility comes at the cost of complexity, as more code paths mean more opportunities for edge cases to break. The agent's kernel is more specialized to the exact KDA formulation, resulting in cleaner code that proves more robust on a variety of input shapes.

The entire optimization process took a few hours of agent compute time, compared to the days or weeks of manual tuning that experts usually contribute to kernel generation. This represents a fundamental shift in how performance-critical kernels can be developed: describe the algorithm, provide reference implementations, and let the agent explore the optimization space.

Limitations and Next Steps

In many cases, generated kernels generalize across shapes. In this case, the generated kernels do not. Therefore, we generate separate Triton kernels for each input shape. A next step would be to pass both of these kernels to MakoraGenerate, and ask it to produce a kernel that maintains performance across both shapes. The agent could deploy conditional logic, or perhaps discover an implementation that works across a wider variety of input shapes.

Another issue is the failing compile of the FLA kernel on the larger shapes. This could be an issue that we just didn’t put enough effort into debugging. If someone gets it working, let us know and we’ll update this blog post.

Conclusion

KDA exposes the limits of general-purpose compilers like torch.compile, which cannot recognize that a recurrent state should live in fast on-chip memory rather than making round-trips to HBM every token. The fix required domain-specific restructuring: keep the state in SRAM across the sequential loop.

MakoraGenerate, the industry-leading GPU kernel coding agent, independently identified this expert insight automatically, achieving 5.6 to 7.8x speedup over Inductor and matching hand-optimized baselines in minutes rather than weeks of manual tuning. As new attention algorithms and new hardware accelerators continue to evolve, this kind of automated kernel optimization shifts becomes essential to keep up with progress in the field.

[1] Kimi K2: Open Agentic Intelligence (Kimi et. al., 2025), https://www.arxiv.org/abs/2507.20534

[2] Kimi Linear: An Expressive, Efficient Attention Architecture (Kimi Team et. al., 2025) https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.26692

[3] Flash Linear Attention Github Repo, https://github.com/fla-org/flash-linear-attention/tree/main/fla/ops/kda

Latest

From the blog

The latest industry news, interviews, technologies, and resources.